Recently I spent some time at the the University of Cincinnati Classics Library playing with their trial of the Digital Loeb Classical Library. This new subscription resource became available in mid-September. I’ll start with some commentary and screenshots on how the Digital Loeb works, and follow with some more big picture thoughts.

As a note, there are many older, out-of-copyright Loeb volumes that have been freely available in digitized versions for some time. E. Donnelly’s Downloebables first made them easily findable, and Ryan Baumann’s Loebolus offers an alternative format. I also recently ran across a fun tumblr blog that collects snippets of some of the antique translations that appear in these older Loebs.

What Digital Loeb Does

When a user arrives at the Digital Loeb site, the search box is prominent, but there are also browse options available at the left. The user is given the choice of browsing Author, Greek Works, Latin Works, or Loeb Volumes (arranged by number).

Each volume can thus be approached through a table of contents page, which reproduces the print volume’s table of contents, except that each section heading is clickable, and one can also search within the entire volume.

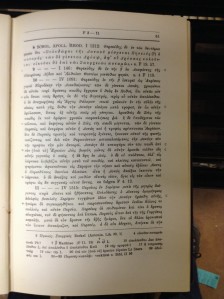

Although I’ve just begun to explore the site, two things have already become clear: the site’s aesthetic is fairly elegant and generally pleasant, and the overall structure of the site very closely replicates the print versions of the Loeb volumes. The site is giving me the clear message that this is a digitized version of the existing Loeb Classical Library, not a re-envisioning of the LCL for an internet environment.

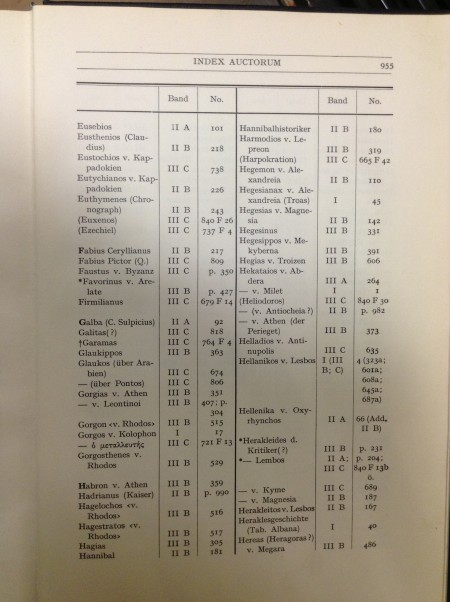

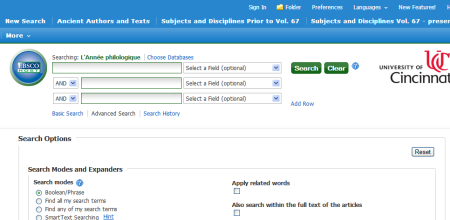

Librarians always skip basic search boxes and go straight to Advanced Search, so I did that. It defaults to a Boolean structure, with two boxes connected by AND but the option to add more boxes, and to change to OR or NOT. The fields available to search are: Author, Editor/translator, Front and back matter, Main text, Notes, Recto, Verso, Work Title, and DOI (Digital Object Identifier). (I once wrote an intro to DOIs, if you need a refresher on that.)

Any of the fields can be searched using Greek characters, using a handy pop-up keyboard; this makes searches of the Greek text quite easy. The user can also select a period to limit the search chronologically (only by 100 year intervals, i.e. 600 BC – 500 BC, and note that one cannot select more than 1 period – are authors whose writing lives took place in two different centuries out of luck?)

I did a complicated Boolean search to try to identify a remembered quotation for a friend, and blogged about it last week.

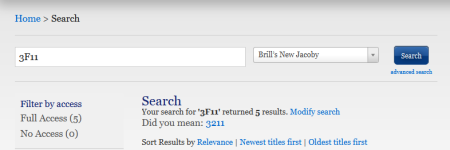

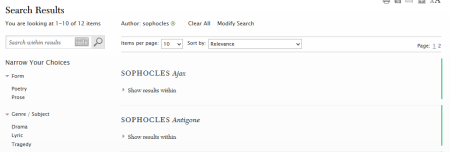

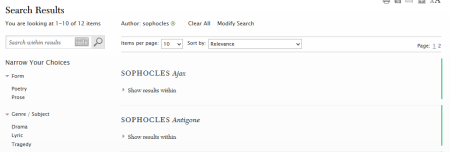

Below are the results of a simple author search for Sophocles. Works display in alphabetical order, and one can ‘facet’ the search (narrow it further) using the left column in results (although in this case the choices are not particularly useful). The one user experience problem I had using the Digital Loeb happened here – I found it not obvious how to get to the actual text of one of the works in the search results. I first clicked on Show Results Within under the entry and got nothing (since I had done an author search, not searched the text of the works). It turned out I needed to double-click on title of the work to get to the actual text.

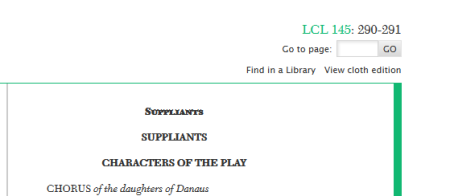

Another aesthetic touch I really liked – the green line on the screenshot above, and the green edge of the digital page of Sophocles’ Antigone below, carrying on the color-coding of the print Loeb volumes.

Once inside a work, the Tools at the bottom of the page allow the user to search for words within that text, again using English or the pop-up Greek keyboard.

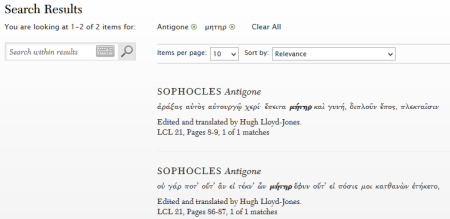

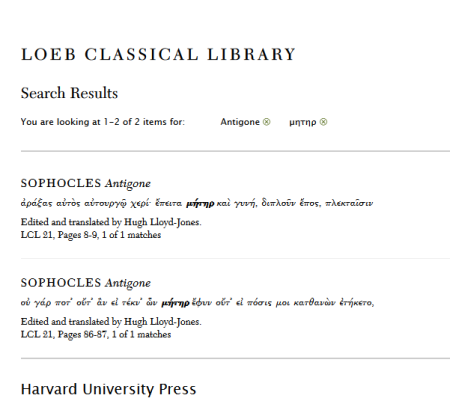

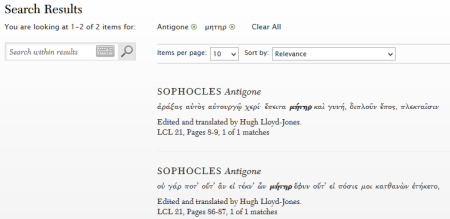

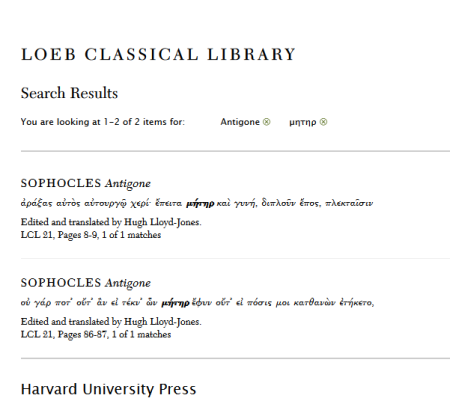

Below are the results of a ‘search within’ for a specific Greek word. Note that it seems as though there is not any sophisticated lemma searching going on here – the search engine can only do exact character matches (and ignores accent). So this is useful if you are trying to place a Greek quotation, but not useful if, for example, you wanted to investigate all discussions of “mother” in Antigone – for that, TLG would be the right resource.

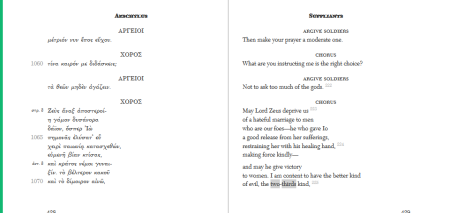

If you want to make these results printer friendly, they are very pleasing-looking. (In general it didn’t seem possible to print more than one page of a text at a time, but I might have missed a way to do this, so please correct me if I’m wrong!) In addition to printing a page/search result/etc., one can save it (to a personal account, discussed in more detail below), email it, or share it on social media. I tested sending search results to twitter, and they were visible to those not currently subscribed to Digital Loeb (thanks, @s_margheim and @magistrahf!) It’s also easy to change the font size, a nice touch for those of us quickly approaching ‘reading glasses age’.

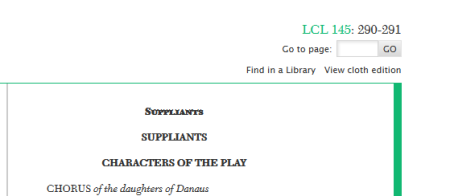

To navigate within a text, the experience very closely replicates paging through the print volume. One can move forward or back one page at a time using arrows on the page images, or go to a specific page using the box at the top right corner of the screen (see below). There isn’t, as far as I found, any easy way to jump to a specific line number within the text you’re looking at, however. I wanted to get to line 1060 of Aeschylus’ Suppliants at one point, and found myself guessing what page it would be in the volume by seeing what page I was on and how many lines appeared per page. It later occurred to me that it would have been faster to ‘search within’ the text for “1060,” but that seems like a silly workaround to have to resort to when navigating by line number is such a fundamental way of interacting with a text (including print Loebs!) Note that the Green “LCL 145” below is hotlinked and will take you to the table of contents for the volume – I probably would not have stumbled across this early on, but instead learned it from the Frequently Asked Questions page at the site.

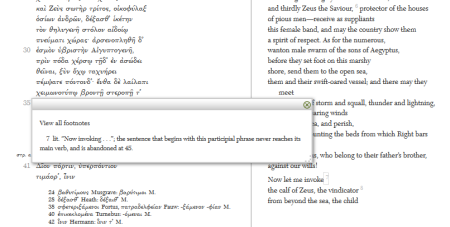

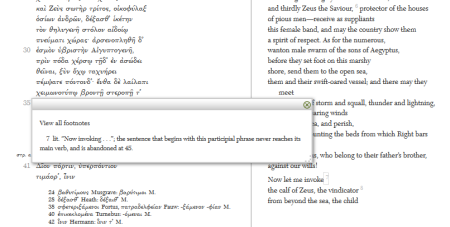

Happily, the footnotes in the texts do take advantage of the digital environment and pop up if one clicks on them:

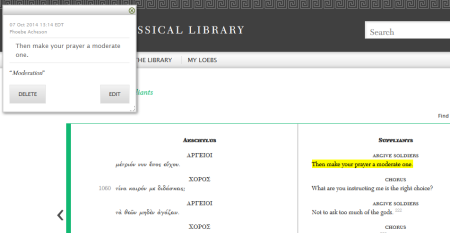

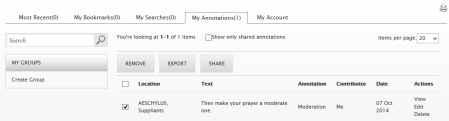

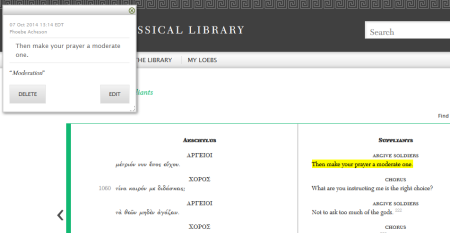

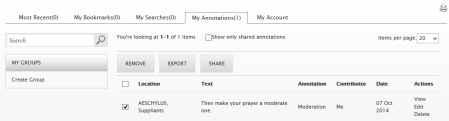

Several additional features are available to users who sign up to have an account. The only information one is asked for is name, email address, and a password, so presumably one could remain pseudonymous if one wished. The web site did not mind that I was on guest wifi at the University of Cincinnati and only using a trial of the site; I was able to create a personal account with no trouble, using a gmail address. Account features include creating bookmarks, saving searches, and creating annotations. One simply highlights a word or phrase in the text and can add a note.

The ability to share one’s annotations with other account-holders, and especially the ability to create groups with which one can share, makes annotation an excellent teaching tool on a campus with a subscription: all students could be asked to set up accounts, and the instructor could share annotations with the group or ask them to share amongst themselves.

What Digital Loeb Does Not Do

The Digital Loeb does not do much if anything to advance the scholarly conversation around digital texts in classics. It’s a closed, subscription resource; as far as I can tell its texts cannot be downloaded for any purpose at all (for example, to do specialized scripted searches looking for patterns in style or content across texts, like Tesserae has done with Perseus texts). It hasn’t got lemma searching (like TLG). It hasn’t got grammatical or dictionary support for students (like Perseus). It’s not in dialogue with developing digital text projects involving multitext, annotation, or commentary (like Homer Multitext, the Digital Latin Library, Arethusa, Dickinson College Commentaries, and many other worthy projects I hope I don’t offend by not mentioning here). Now, was Digital Loeb required to do any of those things? Of course not. But is it appropriate to point out these limitations, and even mourn a lost opportunity? I think so. Interested in reading further commentary on these sorts of issues? See Greg Crane’s long essay from Feb. 2014 on the Digital Loeb in contrast with his vision of Open Philology; and another essay from Sept. 2014 now that Digital Loeb is available.

Should You Subscribe to Digital Loeb?

If you really like it, and you’re an individual, it is available at an individual price of $195 for the first year and $65 for each additional year. You can figure out for yourself what it might cost to buy a full print set of Loebs and update as new volumes are released – my guess is you come out ahead even if you subscribe as an individual for 20 years! But there’s not any way for an individual to have trial access – you’d need to talk to a librarian, so if you’re not affiliated with an educational institution, that becomes tricky. (If this is you, I am sure your local public library would be willing to apply for a free trial on your behalf, but I am sure many non-academic people would never think to ask.)

Pricing for institutions more complicated and less transparent, and one is encouraged to email directly for a quote for an individual library (or presumably consortium). Subscription and perpetual access plans are offered, which is nice for those with deep pockets and fatigue with the ‘annual subscription for digital resources’ problem. There is also a note that secondary schools are offered discounts for institutional pricing. Anecdotally, what I have heard is “it’s expensive.” What that means is of course highly variable.

If you’re a librarian reading this and pondering what your institution should do, it certainly makes sense to do a trial and beg, bribe, or threaten students (undergrads and graduate students) and faculty to give you feedback. I’d be most interested in hearing from students, plus faculty who teach the languages at the middle levels and/or have a special interest in pedagogy. My guess is a lot of people will like the Digital Loeb – it’s aesthetically pleasing, and easy to use, and lets you put the whole Loeb Library on your computer (maybe even in your hand – I wasn’t able to test it on a iPad, but I see no reason it wouldn’t work, and the effect would basically be an e-book – it’s just the right size for an iPad mini!). For the librarian, the choice is tricky – it’s a pretty product, but we mostly already get and will continue to get the print Loebs. Does the Digital Loeb add much but convenience and ease of finding passages? It doesn’t have lexical or grammatical tools; it does have quality modern translations, which the more digitally sophisticated Perseus or TLG lack. Does the price your institution has been quoted make this a good deal for you, or not?